English | Spanish

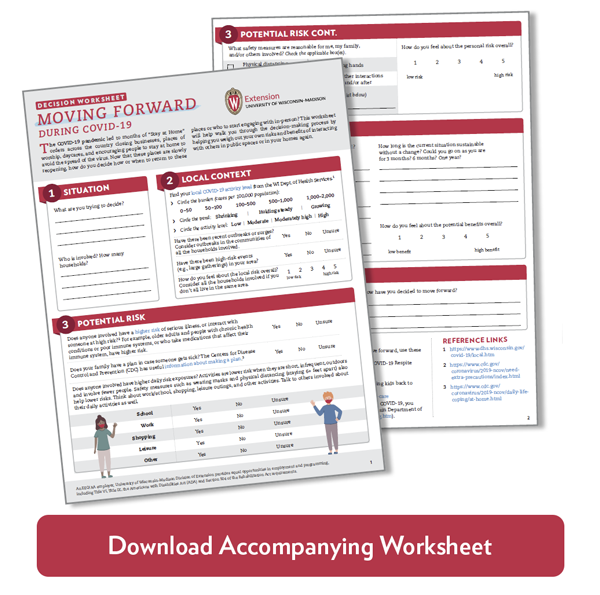

Download Printable Guide (PDF)

The COVID-19 pandemic led to months of “Stay at Home” orders across the country. People were encouraged to stay at home to avoid the spread of the virus. Businesses and workplaces, places of worship, schools, and daycares were closed. Until most people are protected by vaccinations and health officials tell us we can relax our safety measures, it is important to continue being cautious with our behaviors and interactions. How do you decide how or when to return to these places or who to start engaging with in-person? This guide will walk you through the decision-making process. It will help you weigh out your own risks and benefits of interacting with others in public spaces or in your homes again.

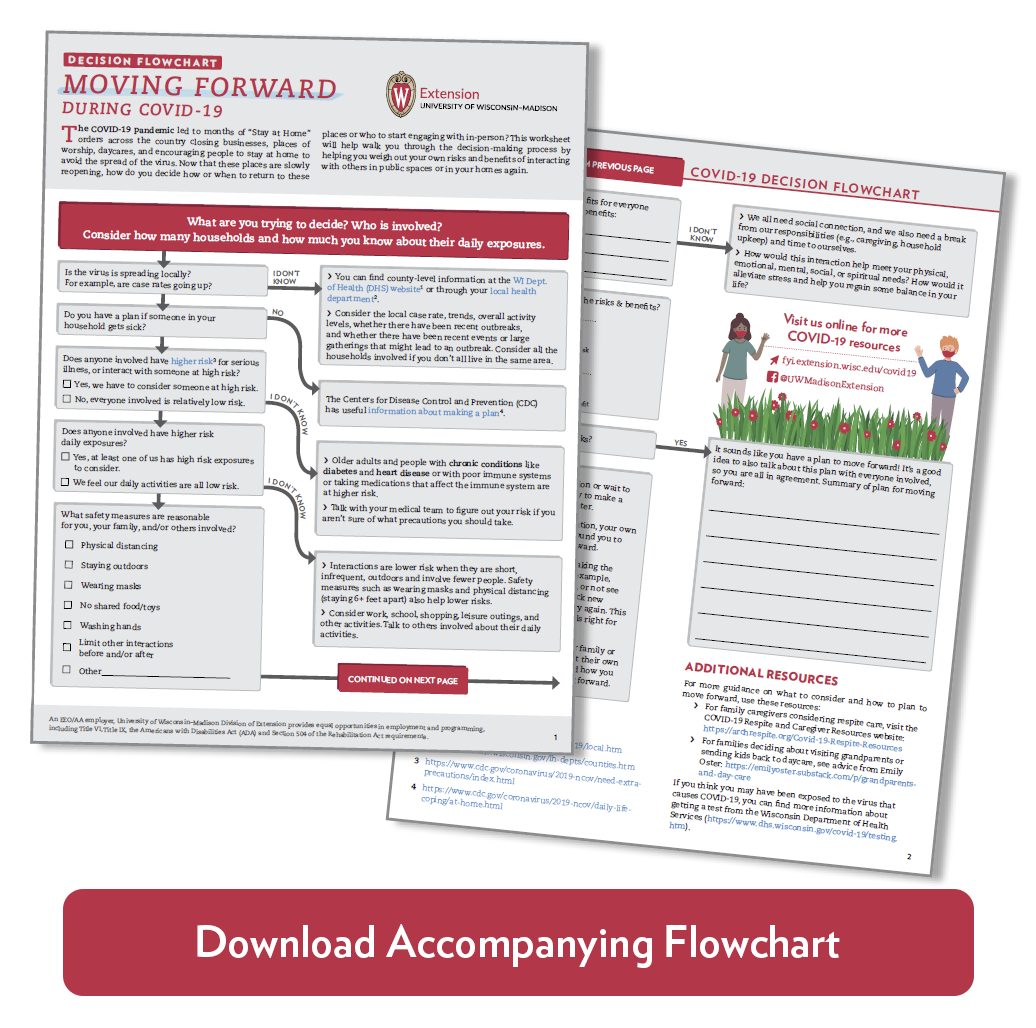

Before you start, consider: What interaction are you thinking about, and who is involved? Examples might include deciding when to see family, visit grandparents, send your children back to daycare, set up respite care or in-home help, or go to a barbeque or other event. Each section in this document has several questions to consider, with more information and guidance for each. You can also download a worksheet or flowchart to help you think through your decision or our use our online interactive version.

Consider: Local context

What is the local trend in cases and deaths from COVID-19?

Check with the Wisconsin Department of Health Services to understand the COVID-19 activity level in your area.

- Are cases increasing, decreasing, or holding steady? Is the activity low, moderate, or high?

Your local health department will also have useful information to help you understand local trends and issues.

Other useful information includes:

- The percentage of positive COVID-19 tests in your county. Lower numbers (less than 5%) show that there is enough testing to get the virus transmission under control, and you are less likely to cross paths with the virus.

- The doubling rate of infections (that is, how long it takes for the number of cases of COVID-19 to double). This information tells you how fast the virus is spreading. Higher numbers mean the virus is spreading more slowly and transmission is under control.

- You may be able to find this information from your county health department, or from one of the data resources listed below.

Have there been recent outbreaks or surges?

An outbreak is a sudden increase in the occurrence of a disease at a particular time and place. For example, several long-term care facilities and prisons have seen an increased rate of positive cases of COVID-19 due to the number of people in close proximity to one another. You might find out about outbreaks from the news or from the county health website. Remember to think about outbreaks in the communities of all the households involved, if you don’t all live in the same area.

Have there been recent local events that may lead to a surge, such as large gatherings or events?

We are learning that many new cases of COVID-19 are arising when a very infectious person (typically unaware that they are contagious) has attended a large gathering, leading to a localized outbreak. Remember to think about events in the communities of all the households involved, if you don’t all live in the same area.

What is the local healthcare system like?

Healthcare in rural areas can often handle fewer cases than in urban settings, so it is important to know what your closest clinics and hospitals can handle and whether they are currently dealing with a lot of cases or very few.

Consider: Possible risks

How many other households are involved, and how much do you know about their day-to-day activities and possible risks?

It might be helpful to talk about the questions below with the other individuals or families involved so that you are all on the same page.

What is the personal risk for the people involved, whether you are the host, the guest, or a participant?

People who are older or have chronic health conditions such as diabetes and heart disease, or who have poor immune systems or take medications that affect their immune system, are at higher risk of complications and poor outcomes if they get COVID-19.

Does your family have a plan if someone gets sick?

For example, the CDC recommends that someone with symptoms of COVID-19 use a separate bedroom and bathroom to prevent spreading the illness to other family members. For family caregivers, the Greater Wisconsin Agency for Aging Resources (GWAAR) has step-by-step advice (PDF) for developing a plan for if a caregiver gets sick.

What are the chances that someone involved (you and/or the person or family you are hoping to see) has been exposed to the virus?

Assessing the distance, time, activity, and environment, frequency of outings, and adherence to safety precautions like mask wearing can help you think about the risk.

- Short, infrequent outings like grocery shopping carry relatively low risk, while essential workers such as medical professionals may have much higher risk of being exposed. Safety precautions such as wearing a mask or other face covering, keeping a physical distance from others, washing hands often, and staying outdoors also play a role in reducing the risk of spread.

- People who live or work in congregate settings (where a number of people meet or gather and share the same space for a period of time) such as a child care center or residential care facility, or who live in a high-density neighborhood may have more risk in their day-to-day exposures.

What is the worst-case scenario if someone gets sick?

Think about consequences to your own family, as well as the possible effects for others with whom you have contact.

Overall, keeping your number of contacts low is an important way to minimize your risk.

Consider: Possible benefits

What are the possible benefits of the interaction? How would it meet physical, emotional, mental, social, or spiritual needs?

We all need social connection, and we also need a break from our responsibilities (such as caregiving and household management) and time to ourselves. How would the interaction you are considering reduce stress and help you regain some balance in your life?

What are the short and long-term consequences of NOT meeting those physical, emotional, mental, or social needs?

Grief, loneliness, despair, and burnout can result from ignoring our personal and self-care needs. These feelings should not be ignored.

Is it possible to meet these needs in other ways?

Phone and video options are now available for many activities, including faith services and even virtual respite care for family caregivers.

How long is the current situation sustainable without a change?

What was workable for 1 to 2 months might not be sustainable for longer periods of time as we face the possibility of ongoing waves of outbreaks. What arrangement would balance your family’s safety and well-being in a way that is possible over a longer period?

Consider: Timing and context

Are there any upcoming events that would increase or decrease risks in a significant way?

Consider things like children going back to school, necessary work trips, or other changes to the number or type of contacts your family typically has.

How can you make the interaction as safe as possible?

How can you make the interaction as safe as possible? Staying outdoors, wearing masks, frequent hand washing, and maintaining physical distance (staying 6+ feet apart) can all help reduce transmission risks. These are important until the spread of the virus is very low, even if you’ve been vaccinated! Consider virtual options if it is not possible to take safety precautions. For family caregivers, virtual respite is becoming an option in many communities.

Next Steps

Talk with your family or those you want to interact with about their own thoughts on the questions above, and how you can all feel most comfortable moving forward. It’s important for everyone to be on the same page about how you will interact and what steps you will take to protect each other.

If you still feel conflicted, try breaking the decision down to two options. For example, should we see family this weekend, or not see them at all until next year? Then pick new options that are less extreme and try again. This exercise might help clarify what feels right for your family.

If you don’t feel like the risks are worth it, it’s okay to say no to an invitation or wait to change your routine. It’s also okay to make a decision and change your mind later. Continue to track the local situation, your own needs, and the needs of others around you to decide when and how to move forward.

Ultimately, the decision of whether and how to move forward is very personal. Staying outside, wearing masks, practicing physical distancing (staying 6+ feet apart), and washing hands well and frequently can all help support safe social engagement. The best advice is to come to a decision you all feel comfortable with and enjoy every minute of it.

Additional Resources

For more guidance on what to consider and how to plan to move forward, consider these resources:

- For family caregivers considering respite care, visit ARCH National Respite Network’s COVID-19 Respite and Caregiver Resources page: https://archrespite.org/Covid-19-Respite-Resources

- For anyone trying to decide how to move forward, visit the Decision Tool from the Wisconsin Department of Health Services:

https://www.dhs.wisconsin.gov/covid-19/decision.htm

For general advice on managing risks while moving forward these are a few articles to consider:

- From the Wisconsin State Journal: https://madison.com/wsj/opinion/column/dr-james-stein-how-to-manage-covid-19-risk-as-you-leave-your-cocoon/article_5167d99a-90be-534f-8117-8b194c6c8809.html

- From Wisconsin Public Radio: https://www.wpr.org/it-safe-visit-family-and-friends

- From PBS News Hour: https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/how-to-form-a-covid-19-social-bubble-or-quaranteam

- From the New York Times: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/09/well/live/coronavirus-rules-pandemic-infection-prevention.html?referringSource=articleShare

There are many tools that can help explain the local spread of the virus, summarize trends, and make predictions about what is to come. Here are some that might be helpful:

- Wisconsin Department of Health Services (WI DHS) COVID-19 Data Dashboard has information on case rates, deaths, hospital capacity, and facility investigations at both the state and county levels: https://www.dhs.wisconsin.gov/covid-19/index.htm

- WI DHS also offers color-coded maps of the total number of cases and case rates, which help provide an interpretable comparison across counties: https://www.dhs.wisconsin.gov/covid-19/cases-map.htm

- Many counties have their own data dashboard summarizing the risk to the public health. You can locate your county health department here: https://www.dhs.wisconsin.gov/lh-depts/counties.htm

- The Harvard Global Health Institute has a COVID Risk Levels Dashboard that shows county-level data across the U.S.:

https://globalepidemics.org/key-metrics-for-covid-suppression - COVID Act Now summarizes infection rates, positive test rates, hospital capacity, and contact tracing at the national, state, and county levels: https://covidactnow.org/us/wi?s=44750

- The COVID-19 County Tracker from the University of California – San Francisco allows users to visualize a rich array of data, including total and new cases and deaths, doubling time, and estimated ICU beds needed. However, users should know that this resource is less intuitive to use than other resources. https://comphealth.ucsf.edu/app/buttelabcovid

- Johns Hopkins University offers county-level COVID-19 Status Reports, accessible here (search by state and county):

https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/us-map

Social connection is really important for our well-being. So are many other factors, including food and financial security.

- For state-level information about food resources and programs: https://fyi.extension.wisc.edu/covid19/2020/05/07/food-resources-to-help-get-through-covid-19

- For ideas and resources on healthy eating during COVID-19: https://nutrisci.wisc.edu/nutrisciextension/nutrition-news

- For information about food safety during COVID-19: https://fyi.extension.wisc.edu/safefood/author/bhingham

- For financial resources and information: https://fyi.extension.wisc.edu/toughtimes/covid-19-financial-resources

- For additional tips on how to get through social distancing: https://fyi.extension.wisc.edu/covid19/category/topics/families/stay-at-home-tips

- For information about new scams and fraud attempts that have emerged during COVID-19, see the Federal Communication Commission’s COVID-19 Consumer Warnings and Safety Tips: https://www.fcc.gov/covid-scams

- The American Red Cross of Wisconsin Virtual Family Assistance Center provides support to families struggling with loss and grief due to the ongoing Coronovirus pandemic, including special virtual programs, information, referrals, and services to support families in need: https://www.redcross.org/virtual-family-assistance-center/wi-family-assistance-center.html

Authors

Kristin Litzelman is an assistant professor in the UW–Madison School of Human Ecology and a Division of Extension state specialist. Deborah Moellendorf is a professor and Division of Extension educator. Sara Richie is the outreach program manager for the the Division of Extension Life Span Program. Ruth Schriefer is a professor and Division of Extension educator.

Download Article

How is Wisconsin responding to social isolation and loneliness during the COVID-19 pandemic? Results from an Extension survey of partner organizations

How is Wisconsin responding to social isolation and loneliness during the COVID-19 pandemic? Results from an Extension survey of partner organizations Families Under Stress: Assessing Caregivers’ Adaptation, Coping, and Resilience through the COVID-19 Pandemic

Families Under Stress: Assessing Caregivers’ Adaptation, Coping, and Resilience through the COVID-19 Pandemic Families Under Stress: New Research Shows How Caregivers Have Adapted and Found Resilience throughout the COVID-19 Pandemic

Families Under Stress: New Research Shows How Caregivers Have Adapted and Found Resilience throughout the COVID-19 Pandemic Seguimos adelante durante COVID-19: decidir quién, cuándo y cómo

Seguimos adelante durante COVID-19: decidir quién, cuándo y cómo