APPENDIX – Insect Pest Management – 3.0

Insects attack all types of turfgrass and ornamental plants grown in Wisconsin. If left unchecked, these attacks can, on occasion, be devastating. The best way of successfully combating insect pests is to know the life cycle of the insects involved: when they are active, the conditions that favor their increase, the natural controls that affect them, and the most susceptible stages for cultural or chemical control.

In this appendix, we will expand upon the general principles of pest management as they relate to managing insect problems.

Insect Management

There are many approaches to insect management in turf and ornamental plants. Some work better for certain plants or insects than for others.

Prevention

Examples of prevention include inspection of all incoming plant material before using it in a landscape or interiorscape—do not purchase infested plants or cuttings.

When purchasing container-grown or balled and burlaped nursery stock, only buy plants that have been certified as pest free. Soilborne insects (e.g., Japanese beetle grubs) may be introduced into a site on infested stock.

Using sterile planting media in interiorscapes will help prevent growth of algae and fungi that can support insect pests such as fungus gnats.

Insect-Resistant Varieties

Certain varieties of a plant may show resistance or tolerance to one or more pests. No method of control is perfect and there are problems associated with developing and using resistant varieties. However, using resistant varieties can be a powerful tool in managing insects.

Biological Control

Natural enemies are perhaps the most important means of controlling insects that attack turf, shade trees, evergreens, and flowers. Harmful insects usually don’t flourish in landscape plantings because many different types of plants are present—in other words, there is no monoculture. Because of this, pest populations tend to remain small enough that natural enemies can keep them in check. This often reduces the need for insecticides in landscape plantings.

Natural Enemies. Every pest insect and mite is controlled to some extent by other organisms called natural enemies. The main groups of natural enemies are:

- Predators

- Parasitic insects

- Parasitic nematodes, and

- Insect pathogens

Predators.

Predators are mobile and usually fairly active. They tend to be larger than their prey and eat many prey animals during their lives. Examples of insect predators include birds, rodents, bats, predatory insects and mites. Of these, the predatory insects and mites are most beneficial in protecting ornamental plants (Figure 1). Examples include lady beetles, lacewings, hover flies, pirate bugs, and damsel bugs. Spiders are also important predators.

Parasitic Insects. Parasitic insects are the largest and most important group of beneficial natural enemies that control insect pests. Parasitic insects (also called parasites or parasitoids) include stingless wasps and flies (Figure 2). The adults are active fliers that seek out hosts that will serve as food for their offspring. They lay one or more eggs in or on the host, and the parasite larva feeds from the host, eventually killing it. The

parasite larva then pupates, and eventually changes into an adult parasitic wasp or fly, completing the life cycle.

Parasitic Nematodes. Insect-parasitic nematodes are tiny roundworms that parasitize and kill insects. They are most active in moist soil.

Insect Pathogens. There are many types of microorganisms that weaken or kill insects. These insect pathogens, which include various types of fungi, bacteria, viruses, and protozoans, are not harmful to plants, humans, or other types of animals. One example is the bacterial milky spore disease used to help control Japanese beetle larvae.

Approaches to Biological Control

Thousands of types of beneficial natural enemies constantly help reduce pest populations, usually without our awareness. Without natural enemies, it would be impossible to control many pests, even with pesticides. When natural enemies work without human assistance, the result is called natural control. When we purposefully manipulate natural enemy species to reduce pest populations, this is called biological control.

Biological control methods are not available for every pest of every desirable plant, and other methods, such as chemical control and cultural controls, are important, but should be used in ways that do not interfere with the benefits of natural enemies.

There are three broad approaches to biological control or pest insects and mites:

- Importation of natural enemies,

- Augmentation of natural enemies, and

- Conservation of natural enemies.

Importation of Natural Enemies. Importation of natural enemies (also called classical biological control) relies on the introduction of non-native beneficials from other locations. This approach recognizes that many or our most serious pests are not native to North America but have been introduced. Frequently, the most effective natural enemies are those associated with the pest in its native location. Therefore, federal and state agencies search for better natural enemies in other locations, carefully evaluate them to assure that the new natural enemies will not themselves pose any risk, and then release them into the target crop environment with the goal of permanent establishment. This is a very effective method that can result in long-term pest control.

Augmentation of Natural Enemies. Augmentation of natural enemies relies on the routine, periodic release of purchased natural enemies. It differs from the importation method in that the effects are temporary rather than permanent. Several companies produce predatory and parasitic insects, insect parasitic nematodes, and insect pathogens that can be purchased and released for biological control.

Conservation of Natural Enemies. The third approach to biological control is conservation of natural enemies. Beneficial natural enemies, like other organisms, require food, water, shelter, and protection in order to survive. Often, our site and pest management practices can reduce or eliminate these requirements, resulting in greatly reduced natural enemy activity.

Conservation methods reduce interference and mortality factors, or provide needed requirements, to allow natural enemies to thrive and provide us with better biological control. For example, broad-spectrum insecticides are usually more harmful to beneficials than to target pests. By reducing harmful pesticides more beneficial insects will survive to aide in pest control. Although it may often be necessary to use an insecticide, it should be done in a fashion not to interfere with beneficials. This is the true basis of integrated pest management. Often we can choose pesticides that are less disruptive to natural enemies. For example, organophosphate insecticides are much less harmful than carbamate and synthetic pyrethroid insecticides to the predatory mites which are important in the control of European red mite and two spotted spider mites.

Cultural Control

Cultural practices are directed at “weak points” in the insect’s life cycle and are generally something the turf or landscape manager does anyway, such as site selection, sanitation, and controlling weeds. Advantage is taken of the insect’s relationship to its host plant.

Cultural control also involves providing ideal growing conditions for the desirable plants. This includes proper irrigation, mowing, aeration, topdressing, pruning, fertilization, climate control, and plant spacing. By providing good growing conditions, you avoid plant stress. Stress can make plants more susceptible to pests (e.g., drought stress increases a birch’s susceptibility to bronze birch borer attack), as can an imbalance of soil nutrients.

Cultivation. In turf, core cultivation and topdressing reduce thatch that sometimes harbors insect pests.

Pruning. Pruning will keep a plant vigorous and healthy, which will help it fight off pest problems. You can also use pruning to eliminate pests, for example, to remove egg masses of tent caterpillars.

Discarding. At times, you may be better off discarding infested interiorscape plant material than trying to manage the pests. This is especially true of scales, mealybugs, and mites which may be difficult to control otherwise.

Site Selection. Many turfgrass varieties and landscape plants have very specific environmental requirements. Birch trees, for example, prefer a shady site with moist soil conditions. When exposed to excessive sunlight and/or inadequate soil moisture, birches are likely to be under stress and, as a result, most susceptible to infestations of the bronze birch borer. Similarly, some species and varieties of trees are better suited to withstand environmental stresses. For example, maples seem to be very sensitive to soil compaction, while lindens are more tolerant.

Site selection is also important for interiorscape plants. Keeping plants away from heaters, for example, will prevent the hot, dry conditions that are conducive to spider mite infestations.

Sanitation. Sanitation is simply the elimination of materials or locations that favor the pests. Piles of prunings and brush are ideal overwintering sites for some pests. So removing those materials helps reduce local populations of these insects. Similarly, removing unhealthy or dead trees will eliminate breeding sites for many pests. Removing wild host plants from fence rows also helps reduce local pest populations. Sanitation in an interiorscape can help reduce the presence of algae and fungi, which support populations of shore flies and fungus gnats, respectively, in potting mixes.

Weed Control. Weeds provide alternative hosts for many insect pests. They can also harbor plant pathogens vectored by the insects. When insect pest numbers increase sufficiently, the insects will likely attack nearby desirable plants.

Insecticides and IPM

Remember that the problems associated with insecticides are only potential disadvantages. A full awareness of potential drawbacks before selecting and using insecticides usually allows us to use them in integrated pest management programs. To do so, you should:

- Use scouting and a treat-when-necessary approach as opposed to routine Remember that eradication or 100% control is not necessary to prevent economic

- damage. Also, a residual population of pest insects is needed to maintain a population of beneficial insects. Without this residual population, beneficial insects would either starve or move out of the site, setting the stage for future pest problems.

- Carefully time insecticide applications to attack insects at the weakest point of their life cycle. Use scouting to time these applications.

- Use preventative treatments only as a last resort and use the most selective compounds available. Many of the newer insecticides being developed are more selective than older products.

- Be selective in the use of insecticides to control pest populations while minimizing effects on nontarget organisms. For example, spraying blossoming crabapples can result in dramatic losses of honey bees and other pollinators.

We will now discuss these aspects of IPM and insecticide use in more detail.

Scouting for Pests

Scouting—also called monitoring—is the basic cornerstone of IPM. Scouting is a visual inspection of the plants to determine their health and growth stage, what and how many pests are present, and what trends pest populations are following. You can also use scouting to compare pest populations from one year to the next and predict potential pest outbreaks.

To scout effectively, you must be familiar with the early signs of an infestation (e.g., stippling caused by mites or plant bugs). Routine and careful scouting will detect pest populations when they first appear; that is, when they are easiest to control and before damage occurs. By knowing whether or not pests are present in a site, you can replace a routine, preventive spray schedule with fewer, but better timed and more effective treatments.

When a pest is found on only a few plants or in a small area, you can use local control tactics. Spot treatments not only decrease the chance of misapplication or over-application, but use less material than blanket sprays and, thus, help to preserve beneficial organisms.

As you scout, record on a field data sheet the identification, location, growth stage, and severity of all pests present. Take notes on where and what kind of weeds you find. Take notes on anything that you observe that is not normal. These notes can become valuable records of how pest problems develop and what control measures really work. Make a map of a landscape so you can readily identify individual plants or plantings from your records.

Timing Insecticide Applicators

Scouting helps you time insecticide applications properly by letting you know not only when a pest problem is likely to occur, but also which life stages are present. Many pesticides are only effective against certain life stages of the pest. For example, insecticides are most effective against scales and mealybugs during their crawling stage, before they have produced their protective waxy covering. Eggs and

most of the last nymphal stages of whiteflies are tolerant to most insecticides—the adults and young immatures are more susceptible. Some acaracides are not effective against mite eggs. In these cases, repeat applications may be needed to provide effective control. The interval between applications will depend on the residual nature of the pesticide, environmental considerations, when pests are in a susceptible life stage, the generation time of the pest, and the size of the population.

You must also take care to apply a pesticide at the proper stage of plant development: dormant sprays are truly meant to be applied while the plant is dormant or they may cause phytotoxicity.

Pesticides applied against the wrong life stage of a pest are not likely to be very effective. This is one reason why it is important to know the correct identity of a pest as well as its life cycle and biology. In general, control treatments are most effective when they target the life stage of the pest that was scouted as being most numerous. For example, if more larvae are found than adults, use a larvicide; if adults predominate, use an adulticide. Repeated applications may be necessary to gain control of pests with overlapping life stages.

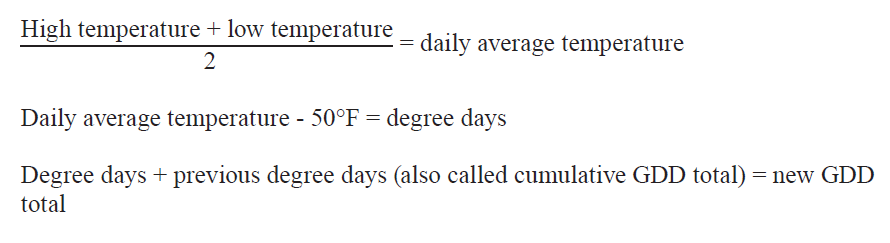

We mentioned in Chapter 1 that insect development is related to temperature and that plant development, too, is dependent on the climate. We can use this dependency, then, to predict when insects are likely to be a problem.

Phenology. Phenology is the study of the life cycle phases of plants and animals as related to climate. The most common technique is to use growing degree days as a predictor of development. If you can match the number of degree days needed for an insect or mite to reach a certain growth stage with the number of degree days needed for a specific plant to reach an easily recognizable life stage, you can use that plant as an indicator plant. Essentially, when the plant reaches the appropriate life stage, you will know that the insect or mite has reached its particular growth stage.

This information gives you one more tool in predicting when a problem might occur. It will help you better time preventive sprays (if you use that approach) and can be useful in scouting. There is no need to scout for ash plant bug nymphs, for example, before enough degree days have accumulated for eggs to hatch.

Phenology is very important in timing insecticide sprays to woody plants. See the box below for instructions on calculating growing degree days and for examples of indicator plants. For more information and examples, see UWEX publication A3597, Woody Ornamentals Pest Management in Wisconsin.

Growing Degree Days (GDD) are a cumulative total of Degree Days (DD) above a base temperature. The most common base temperature used is 50°F. To monitor insect development using this system, you will need a maximum/minimum thermometer to obtain the daily high and low temperatures for a 24-hour period.

Use the following formulas to calculate GDD:

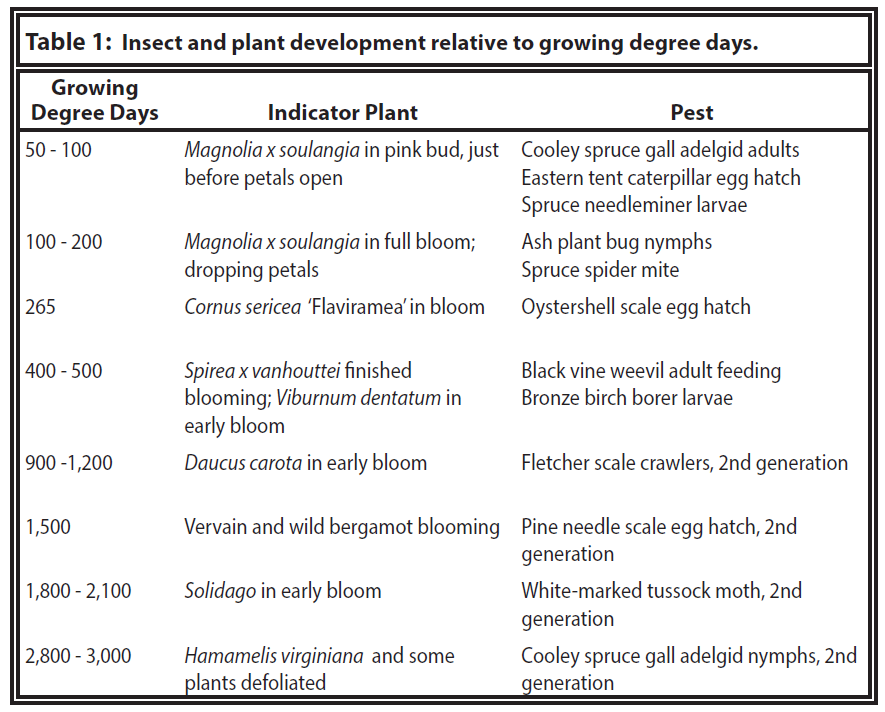

Examples of how growing degree days relate to the development of insect pests and indicator plants are given in table 1.

Need-Based Spraying

As we wrote earlier, scouting helps you determine when pesticide applications are actually needed. Spraying only when necessary will help you avoid the problems associated with preventive or reactive sprays (discussed below). In addition to spraying at the right time, you should target the application to just those plants or areas that require treatment.

Problems with Preventative Sprays. Preventive, or calendar, sprays are made in anticipation of a pest problem. They can sometimes be useful, as when pests are present or if a major pest outbreak is expected in the area. They can also be useful with pests like leafminers and borers which are difficult to control once larvae become active.

However, managing all your pest problems with preventive sprays has significant drawbacks. At the top of the list are unnecessary risks to the environment and a waste of time and money that result when needless applications are made. There is also the risk of pesticide resistance developing in pest populations. Finally, if you do not know what the pest pressure is before you spray, there is no way of evaluating your management program. Thus, there is little chance of making your program more effective and economical.

Problem with Reactive Sprays. Reactive sprays are made after a pest has unexpectedly caused significant damage. This situation is usually a result of insufficient scouting. Problems with using a reactive approach to pesticide use include:

- Irreversible damage to the plants has already occurred,

- You may have missed the pest life stage that is most susceptible to control efforts, and

- The pest population may be large and diverse enough that multiple applications are needed to bring it under control.

Weather Concerns. Insecticide sprays should be made to dry foliage or bark when rain is not expected for several hours. If the spray dries before it rains, a reapplication is usually not necessary. Try to make applications when the temperature is between 50° and 90° F. Pesticides may be ineffective below this range and cause phytotoxicity when it is too warm.

Application Considerations

Getting an insecticide to the insect is as important as applying it at the right time. Whiteflies, for example, occur on the underside of leaves and most life stages are stationary and so do not crawl over treated surfaces. Thus, good canopy penetration will be essential to controlling whiteflies. You may want to space plants a little farther apart to allow for better penetration. Avoid application techniques that leave most of the pesticide residue on the upper surfaces of leaves. You need spray equipment that produces droplets less than 100 microns in diameter to get penetration into these areas.

The choice of contact or systemic insecticide will depend on the pest problem and will influence other aspects of the application. For example, good coverage is especially important for contact insecticides because they do not travel within the plant to a pest feeding site—they must be deposited everywhere the pests are located.

Insecticides that have systemic or translaminar properties tend to be more effective than contact insecticides for green peach aphid control, provided a sufficient amount of insecticide reaches the aphid feeding sites. Contact insecticides, however, may be very effective against other aphid species.

Contact insecticides used to control scales and mealybugs must be applied during the crawler stage of these insects. Repeated applications are therefore necessary to contact the susceptible stages as they are produced. Spray intervals will depend on the residual effectiveness of the insecticide used, which may vary from 0 to 3 weeks. The inclusion of a spreader-sticker can improve coverage, penetration, and residual activity, although the risk of phytotoxicity may be increased. Good coverage is important for contact insecticides. Insecticidal oils and soaps can sometimes be effective, killing more life stages of these pests than many contact insecticides, but they provide no residual control. Again, thorough coverage is critical.

Systemic insecticides may kill actively feeding stages of scales and mealybugs, assuming adequate amounts of insecticide are translocated to the feeding site. Systemics will not kill the egg stage. An additional application may be necessary after 3 to 4 weeks if the residual activity of the systemic is inadequate after this time period in order to kill newly hatched insects.

Contact sprays to control adult leafminers should be repeated at 3 to 4 day intervals to kill those adults that continue to emerge from pupae during the 10 to 14 days following an initial treatment. Systemic insecticides can be very effective against the larvae.

Pests of Turf

Healthy, vigorously growing turf is the best defense against insect damage. In fact, healthy turf not only withstands considerable insect activity, it usually abounds with insects. Among them are beneficial species that feed on harmful insects and mites, help break down thatch, and add to the overall soil condition.

Proper mowing, fertilization, and watering practices help keep turf healthy and are therefore important parts of an insect management program. Likewise, weed control is important. Not only do weeds weaken turf and make it more susceptible to insect damage, in dense patches they can harbor insect pests that eventually invade desirable turf.

Insect Pests of Woody Ornamentals

Most established ornamental trees and shrubs — those that are at least 3 years old and growing vigorously — can withstand considerable insect damage without jeopardizing their health. In most landscape situations, managers will devise insect control strategies that reflect the value they place on the appearance of their trees and shrubs. All managers, however, occasionally will confront insect infestations that can seriously injure woody ornamentals.

Flower Gardens

Insect control in outdoor flower gardens varies according to the aesthetic value of the particular garden. Some municipal gardens and most botanical gardens, for example, are showcase plantings, and most managers will not tolerate an insect invasion that tarnishes plantings or floral beauty. In contrast, managers of low‑maintenance plantings, such as scattered gardens in parks, will respond to insect problems as they appear, and, in some instances, may opt for no control at all.

The type of control strategy — preventive or curative — the manager employs, the extent of an infestation, and the size of the infested garden will dictate what kinds of cultural and chemical controls are used. In small gardens, removal of diseased plants or plant parts may be an effective and practical control. In many other cases, however, chemicals will be the primary tools for control, assuming control is deemed necessary.

Aphids, leafhoppers, plant bugs, and other sucking insects are among the major insect pests of flowers. Because these insects are present throughout much of the growing season, repeated treatments are often necessary. Foliar‑applied systemic insecticides may provide effective control for up to 6 weeks.

Mites, which also are sucking pests of flowers, usually go undetected until injury is apparent. Spider mites do leave a clue, however: they spin light, delicate webs over buds and between leaves. Some acaracides are available for controlling these pests.

Caterpillars, cutworms, inchworms, and leafrollers are examples of chewing pests of flowers. Bait formulations of insecticides are more effective against cutworms than are sprays and soil‑incorporated chemicals. The bacterial pathogen Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) is an effective and very selective means of control for caterpillars.

Slugs can be formidable pests in shaded flower beds and heavily mulched gardens. Because these chewing pests cannot survive in direct sunlight, removing rocks, pots, and boards will eliminate daytime hiding places and help diminish slug populations. Chemical baits, sold as plastic traps, granules, pellets, and dusts, also will control slugs when sprinkled between plants.

Biennial Weeds

Infestations of biennial weeds are comprised of both first- and second-year plants. First-year plants, which are usually easier to control, are often inconspicuous and so frequently escape treatment. Second-year plants, though more noticeable, are often much less susceptible to herbicide treatment. Musk and plumeless thistles, for example, are quite easily controlled with 2,4-D in the rosette stage but become quite tolerant to the herbicide after their flower stalks begin to elongate. Mowing to remove the seed-bearing flower stalks gradually reduces the future biennial weed

population.

Perennial Weeds

Perennial weeds are usually the most persistent and difficult to control. Perennial weeds occur as relatively isolated plants, in patches, or can be uniform and dense across an extensive area. They are a problem in turf and in both annual and perennial ornamental plantings.

A few relatively isolated perennial weeds often fail to cause much concern. But they spread rapidly — a single, healthy quackgrass rhizome can produce over 400 feet of rhizomes in less than a year — so it’s important to make maps, noting areas infested with particularly troublesome perennial weeds. Designate infested areas for specific perennial weed control treatment.

Mixed-Weed Infestations

Often, weed problems do not fall into convenient categories. A weed infestation may be comprised of annual, biennial, and perennial weeds. Selection of the most effective management program depends on accurate identification and noting the relative incidence of problem weeds at a particular site. Depending on the types of weeds present, you may have to use several different control methods, perhaps applied at different times of the year, to achieve adequate control.

Predicting A Weed Problem

Weeds that are favored by management practices tend to pose the most serious problems. Obviously, such practices are chosen to meet the growth requirements of the desirable plants. However, weeds that have growth requirements and growth habits similar to those plants will be favored as well and are likely to emerge. For example, grasses have low growing points and are not controlled by mowing; thus, grass weeds can be major problems in turf. Perennial plantings will often have problems with winter annuals, whereas spring-seeded plantings will have infestations

of summer annuals.

By recognizing these relationships and observing what is happening at a site already, you can predict future weed problems. This will allow you to assess what level of control is necessary and to set up a weed management plan even before planting or the next growing season.

Some weed problems can be anticipated and largely avoided. When establishing turf, for example, the most effective measure for controlling quackgrass precedes sodding or seeding. If the site contains quackgrass which can spread rapidly, apply a herbicide to kill the weed before tilling the soil. There is no way to kill quackgrass selectively after turf is established.

Weed Maps. A valuable tool for controlling weeds is a weed map. Normally, seeds produced by annual weeds during the previous year will have the greatest impact during the current growing season, although dormant seeds may create problems in later years. If you have noted on your weed map where annual weeds have gone to seed in previous years, you can anticipate where problems are likely to occur. Using a preemergence herbicide on these potential trouble spots, for example, could head off some problems (e.g., crabgrass in lawns). Likewise, mapping perennial weeds will help you plan your control strategy for these recurring weeds.

Many weeds, including dandelions and quackgrass, are distributed very widely over a broad range of environmental conditions. Other weeds, though are very specific in their site requirements and, therefore, provide clues about environmental conditions at a particular site. In other words, weeds are often the result, rather than the cause, of the poor performance of ornamental plants. Consider the following examples:

- Annual bluegrass grows well in compacted, wet soils, and/or moderately shaded, wet soils.

- Knotweed and pineapple weed are found in compacted soils, such as on athletic fields. These weeds often grow in association with each other, with knotweed germinating in March, about 60 days before the last spring frosts.

- Ground ivy, chickweeds, violets, and moss are very shade tolerant. These species often grow in areas that are too shady for turfgrass.

- Rough bluegrass, heal all, horsetail, and violets are associated with wet, shady areas.

- Prostrate spurge is associated with high soil temperatures and hot locations.

- Sandbur, carpetweed, silvery cinquefoil, and mossy stonecrop are associated with dry, infertile, and, frequently, acidic soils.

Planning Your Weed Management Program

Once you’ve determined the weed problem, you can determine what level of control is appropriate, both economically and aesthetically. For certain ornamental plantings, absolute weed control is the goal. But for many other plantings, complete weed control is not only unnecessary but also impractical. Using turf as an example, weed control is much more important on golf greens than along roadsides (refer to the chart in Appendix F “Principles of Pest Management”). Keep in mind that the weed management goals (i.e., the level of control deemed appropriate) are often subjective and will vary from one planting to another and from one customer to another.

Once you know both the weed problem and the weed management goals, you can customize a weed management program for a site. Determine which prevention, cultural, and mechanical weed control practices best fit into the site management plan. Acquaint yourself with the properties and capabilities of the various herbicides that you might use. Both herbicide choice and rate are influenced by the weed problem, soil characteristics, plant growth stage, and future plans for the site. Special rules related to environmental protection may also limit herbicide choice and rate. Site management practices will also limit your choice of weed control strategies.

Methods of Weed Control

Chemical and nonchemical control measures have a place in a weed management program. Which ones you use will depend on such factors as the site, the desirable plants, the weeds to be controlled, the seriousness of the weed problem, the cost effectiveness of different options, health and environmental concerns, and prevailing social attitudes. The growth stage of the desirable plants is also very important. For example, a plant may be more sensitive to a herbicide when it is a seedling or when buds are forming; the pesticide label will provide information on plant sensitivity. Plants may also be susceptible to injury from nonchemical control efforts. Yew and arborvitae, for example, are very sensitive to stem injury from hoeing when they are young.

Prevention

Keep in mind that it is often easier and less costly to keep weeds out of a site than it is to control them once they become established. In addition, watch for new weeds while scouting weeds. The earlier a troublesome new weed is found, the better the chance of preventing its spread to the rest of the site.

Weeds often get their start in a site from a few seeds that were accidentally planted along with turf or ornamental seed. You can prevent such introductions by planting only tested and tagged seed. Certified seed is high quality and is free of noxious weed seeds.

Mechanical Control

Weed infestations may get their start in mulches, manure, or newly added soil. Recognize the potential for this problem and choose these materials carefully.

Tillage. Tillage for lawn establishment, hoeing, and cultivating are among the mechanical practices that can fit into turf and landscape management.

Tillage prior to planting (e.g., establishing a new lawn) controls weeds by burying the weeds, severing the shoots from the roots, or uprooting plants so they desiccate. Tilling may, however, bring long-buried weed seeds to the surface, where they can then germinate. Small annuals and biennials can be killed by burying, but this won’t work for most perennials (except seedlings) unless done repeatedly. For best results,

till when the soil is dry so roots will have little chance of becoming reestablished.

Cultivation. Though not applicable to all ornamental plantings, cultivation is an effective means of controlling many annual grasses and broadleaf weeds, if it is done frequently. Because most annual weeds germinate within the top 2 inches of soil, cultivation should be limited to this narrow zone. Deeper cultivation can damage roots of desirable plants and can bring buried weed seeds to the soil surface where they will germinate.

Hoeing, Pulling and Cutting. Hoeing and hand pulling weeds are still effective and highly selective methods of controlling weeds in small areas (e.g., small gardens, isolated weed patches). Ideally, remove weeds while they are still small (less than 4 inches) and be sure to remove the entire root system of perennial weeds. In small areas, annual broadleaf weeds can be controlled by cutting them by hand at the soil surface. This approach will not work for grasses because they grow from points at or below the soil surface. Perennials also have growing points at or below the soil surface, so control would only be achieved if you cut them often enough to deplete their underground reserves.

Mowing is very effective in maintaining turf and helping it withstand weed competition. The grass will grow back because its growing point is below the cut surface, but many broadleaves will be controlled. Even grass weeds, such as quackgrass, may be weakened by repeated mowing and will be less able to compete with the desired grass species.

Set cutting levels as high as possible because tall grass produces dense shade that prevents seeds from germinating. Do not remove more than 30% of the turfgrass leaf surface during any one cutting otherwise, “mowing shock” may result, allowing weeds to invade.

Mowing is effective only against tall weeds. It helps reduce the weeds’ ability to compete with the crop and also prevents seed production. It is feasible, but difficult, to control certain tall perennials by mowing. You would need to mow frequently to deplete the weeds’ food reserves to the point that the plants cannot grow back. Mowing is the dominant cultural practice used in turf. Mowing stimulates tillering, which increases turf density and can reduce weed invasion. Turfgrass will benefit from being maintained at an optimal height of cut. Mowing height and frequency have a significant impact on turf growth. Often, the ideal height for grass health and vigor is not the ideal height for a particular use, such as golf. So, mowing height is often a compromise.

Mulching is a means of weed control but is not appropriate for all plantings. Mulches control annuals and biennials by preventing the seedlings from getting light. Perennials are more difficult to control with mulches because they may grow through the mulch (depending on the material) or beyond the edge of the mulch.

Organic mulches (e.g., sawdust, shredded bark) should be applied at a minimum depth of 2 inches on weed-free soil. Be aware that straw and hay mulches often contain weed seeds that could create a future weed problem. Be sure the mulch is kept away from the trunks of trees and shrubs to prevent problems with rodents or diseases.

Inorganic mulches (e.g., sand, gravel, black polyethylene film) provide a weed resistant surface and allow water penetration (except in the case of plastic film that is not perforated). More than one mulch can be used, as when gravel is put on top of black plastic.

Burning. Though not a very popular method of control, gas burners are used occasionally to remove vegetation from sand traps on golf courses.

Cultural Control

Although weeds compete with turf and ornamentals, remember that the reverse is also true: these plants compete with weeds. By using the best management

practices, you can ensure that the desirable plants grow so well that they either shade

out smaller weeds or are vigorous competitors. In essence, anything that helps a

desirable plant will help it compete with weeds.

Several practices help the desirable plants gain a competitive advantage over weeds. For example, planting immediately after the tillage for lawn establishment, which destroys any weeds that had germinated or emerged, gives the grass an even start with the weeds. Weeds that emerge before the grass are much more competitive than weeds that emerge afterward.

Ornamental plants vary in their ability to withstand competition from weeds. Plants that germinate and grow rapidly deter weed growth. Conversely, plants that establish themselves slowly allow weeds to gain a stubborn foothold. Through planning and weed surveillance, you can determine the weed control methods that are most effective and appropriate for your situation.

Plant ornamental plants at the right time and spacing and then manage the plants to stimulate rapid, vigorous growth. This will keep weeds at a disadvantage.

The Weed Management Program in Action

Having a well-thought-out weed management plan that fits well with your total plant management plan should be very reassuring as you approach the busy growing season. It may not be the perfect plan, but it certainly will be a lot more reliable than the hit-or-miss weed control used by some.

Review your plan as spring nears. Most importantly, stick to the plan. Too often in the rush of spring, managers sacrifice weed control or plant safety to save a little time. If your plan appeared the best route to follow earlier, it’s probably still the most effective way to handle the weed problem. Slight modification due to unforeseen circumstances, such as equipment breakdown may sometimes be necessary. But don’t let hurried, poor judgment jeopardize your weed management plan.

Protecting Sensitive Areas

Review the herbicide use plan as it relates to adjacent sensitive areas that might be adversely affected by the herbicide application. Consider neighboring sites as well as the one you’re treating. Remember, for example, that many garden plants are especially sensitive to 2,4-D. Don’t use this herbicide adjacent to gardens where sensitive plants are growing. Worrying about adjacent plants is especially important in turf and landscapes, where plants of different sensitivities are grown close together. Review the chapter “Overspray and Drift” for tips on how to prevent off-target movement of pesticides.

Think about the presence of lakes, streams, or ponds that are near sites you will treat or if setbacks exist. Leave an untreated buffer strip adjacent to bodies of water to catch any runoff from the site that might contain herbicide. Both direct application and runoff water containing herbicide can be harmful to established vegetation on grass waterways and terraces. Keep the applied herbicide in the site you are treating for the greatest environmental safety and for efficiency of the herbicide treatment.

Monitoring The Weed Management Program

You’ve done the best possible job of assessing the weed problems, considered all practical strategies of weed control, and developed and implemented a management plan to the best of your ability. Now you need to monitor the plan to see if it was as good as you thought. Do you need to adjust or modify the plan to better suit your needs?

Weed Scouting

Monitor the success of your weed management program plan as the growing season progresses. Watch for seedling weeds that escape and decide whether a follow-up treatment is necessary to control them. Don’t let escapes get beyond the stage for effective control. Mark the location of escaping patches of perennials on a weed map so that you can consider them when planning future weed management programs. Finally, note any new, unfamiliar weeds and have them identified.

Minimize Plant Injury

If your herbicide choice and rate were appropriately matched to soil conditions or plant growth stage and if you took steps to minimize drift, herbicide injury shouldn’t be a problem. However, conditions like heavy rainfall or unusually cold or hot weather following herbicide application sometimes causes even relatively safe herbicides to cause plant damage.

Weeds Adapt

Weeds have a tremendous capacity to adapt to both cultural and chemical weed control practices. Mowing favors low‑growing weeds that spread vegetatively or produce seed on short flower stalks that escape the blades of the mower. With selective herbicides, there are always some weed species that are not controlled. The initial escapes may not even be noticed, but they will reproduce and multiply. Continued use of the same herbicide treatment results in a proliferation of those initial escapes until eventually you have a different weed problem. This is an example of a weed shift.

Refining Your Plan

With assessing, planning, implementing, and scouting, you have all of the ingredients for a successful weed management program. Your plan may not work perfectly each year and may require some changes. Modify your plan to deal with escaping weeds. Although weeds will adapt to control efforts, continued refinements of your plan should ensure effective weed management in the future.