Congress expands Great Lakes dredging

Everybody knows water flows, but not many people know that the sediment below it does too. That’ s why harbors need dredging, or excavating the gradually accumulated material at the bottom of the water and transporting it elsewhere.

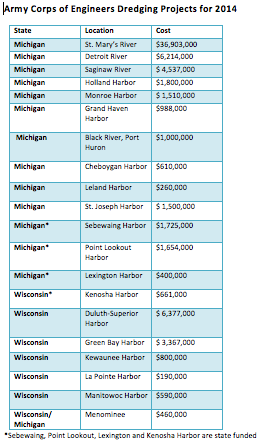

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Detroit District had planned eight dredging projects in Michigan and Wisconsin for 2014 worth $13.2 million. But Congress recently allocated an additional $17.8 million. That allows the district to include eight new projects and increase funding for four of the original projects.

In all, Congress allocated an additional $46.5 million in dredging funds for the entire Great Lakes.

The number of federal dredging projects fluctuates yearly depending on funding, said Jim Tapp, the chief of the Corps’ Technical Services Branch operations office. And “there are always additional needs beyond those projects.”

Lynn Rose, a Detroit District public affairs officer, said a number of sites, including the Detroit River, Green Bay Harbor, St. Mary’s River, Grand Haven Harbor, Holland Harbor and the Milwaukee River, which have high-value commercial traffic, are on the funding list every year. Other harbors may not have that opportunity.

The most recent contract was awarded to King Co. of Holland, Mich., to remove extra sediment from Grand Haven and Holland harbors.

Those two projects, which will begin in early April and end by late May, cost $657,500. Sediment dredged from the two harbors will be put along the nearby shoreline.

According to “Dredging on the Great Lakes,” a Corps report, the sediments are periodically test.

According to “Dredging on the Great Lakes,” a Corps report, the sediments are periodically test.

“The test result dictates where we will put the material,” Tapp said. Outer harbors are primarily made up of sand, which moves up and down the beaches and usually blocks off the entrance to the harbor. That kind of dredged material is clean and usually put on the beach.

The city manager of Grand Haven, Pat McGinnis, confirmed that the sandy sediment in the Grand Haven Harbor was washed in from Lake Michigan, so putting the dredged material near shore is just to “put it back where it is from. There is no environmental concern.”

The sandy material can also help prevent nearby beach erosion, according to the Corps’ report.

By comparison, inner harbors contain more material washed down from upland areas and the drainage basin. Such material “is more likely to be contaminated by the runoffs from farms and city street systems,” which might include petroleum and animal waste, said McGinnis.

According to Tapp, if dredged material is contaminated, it will be transported to a controlled place, usually a confined disposal facility, to make sure it does not harm the environment.

McGinnis said inner harbor sediment in Grand Haven is mixed with organic substances to create topsoil for use in landscaping.

Commercial harbors, which require at least 21 feet of depth, are of great importance for national and regional economies, said McGinnis. That’s where construction materials, like gravel and sand, are shipped in.

If the harbor isn’t dredged, “then we couldn’t get those materials,” said McGinnis, “we couldn’t build the roads. We couldn’t run our power plant. We couldn’t salt our roads.”

The key for maintenance dredging, according to McGinnis, is consistency. “When you let up and you allow these materials to stockpile, it’s really hard to catch up.”

The federal Harbor Maintenance Trust Fund was set up with taxes from shipping and boating industries to support maintenance dredging activities.

With dredging, “you’re never done because Mother Nature continues to bring these sediments back,” McGinnis said.

Detailed dredging information about the harbors in the Great Lakes Basin, including project costs, maps and the date when a harbor was last dredged can be found here.