Feeding Strategies When Alfalfa Supplies Are Short

by Randy Shaver

Introduction

Limited snow cover to go along with a very cold winter leading to abnormally low soil temperatures has caused concern among forage agronomists (Ken Albrecht and Dan Undersander, UW Agronomy Dept.; personal communication) about extensive alfalfa winterkill. The concern about a potential alfalfa winterkill problem has spawned numerous dairy cattle feeding questions with regard to strategies for coping with potentially short alfalfa supplies.

Do a forage inventory

The first step is to take an inventory of forages that are in storage (i.e. corn silage, alfalfa silage, hay, etc.) and normal planned purchases (i.e. western hay) for comparison with forage needs. Remember to include an estimate for feeding losses and refusals into the calculation of forage needs (10% is a reasonable default value). For more information on performing a forage inventory, see the Focus on Forage fact sheet by Brian Holmes, Making a Feed Inventory.

Assess forage availability during summer

Alfalfa fields that are ultimately dropped from production due to winterkill will either be re-seeded or planted to emergency alternative forage crops (i.e. small-grain silage, soybean silage, sorghum-sudan grass silage, short-season corn silage, etc.). Assuming good growing conditions, the new seeding alfalfa fields and these alternative forage crops will provide tonnage to feed the dairy herd, but not until July or August and the quality will be highly variable.

So the inventory versus needs question is really one of how best to manage the feeding program from mid- to late-spring until new-crop forages are harvested in mid- to late-summer. If the inventory versus needs assessment reveals sufficient alfalfa stocks on hand to get through the summer feeding period, then there is no need to adjust herd diets to stretch supply. From the standpoint of cow health and productivity, it is usually better if possible to stretch alfalfa to last longer by feeding lesser amounts than to eliminate it totally from diets. A small negative differential between alfalfa inventory and needs for the summer feeding period may simply mean increasing the proportion of corn silage to alfalfa forage in diets for replacement heifers, milking cows or both and (or) minimizing feeding losses and refusals. A moderate to large negative differential between alfalfa inventory and needs for the summer feeding period will necessitate consideration of more drastic measures depending on the severity of the situation (i.e. feeding lower forage diets, purchasing and feeding higher amounts of high-fiber byproducts, purchasing and feeding higher amounts of hay, or feeding straw). Diet changes aimed at stretching forage supplies should be done under the supervision of a ration consultant.

What are the considerations when formulating a minimum fiber diet?

With the aim of maintaining normal ruminal pH, fiber digestion and milk fat test and preventing acute and subacute ruminal acidosis (SARA) and displaced abomasums (LDA), dairy cattle diets can be formulated or evaluated for chemical fiber (NRC, 2001) and effective fiber (Armentano and Pereira, 1997; Mertens, 1997; NRC, 2001) minimums and non-fiber carbohydrate (NFC) maximums (Nocek, 1997; NRC, 2001).

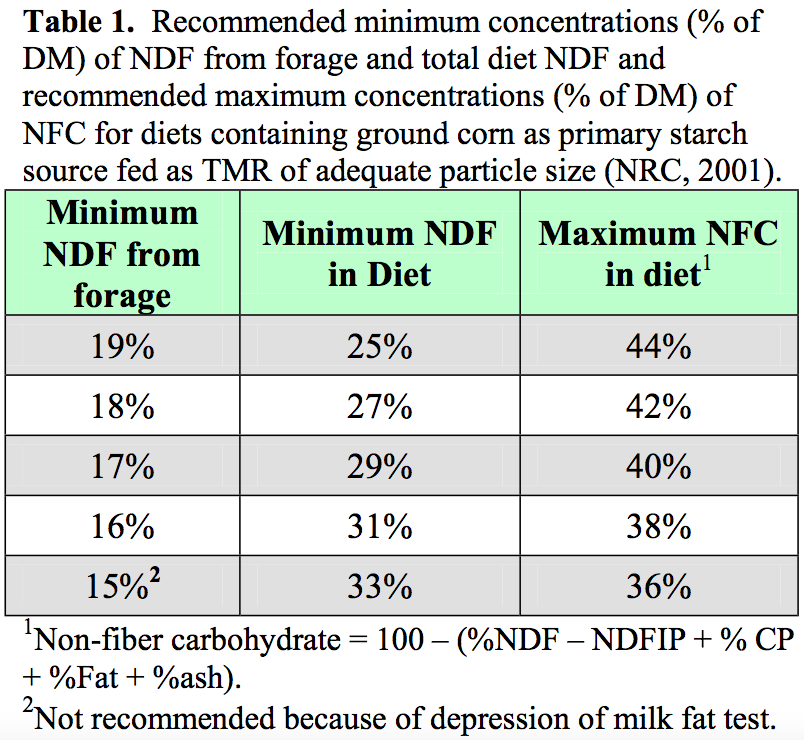

Unlike other nutrients, such as protein and calcium, where requirements are provided in grams per cow per day for specific body weight and milk production levels, fiber “requirements” are merely minimum guidelines aimed at maintaining normal ruminal pH, fiber digestion and milk fat test and preventing SARA and LDA (NRC, 2001). NRC (2001) guidelines for minimum NDF from forage, minimum total diet NDF, and maximum diet NFC are presented in Table 1. Remember that these are fiber minimums and NFC maximums, and not recommended formulation targets for all situations.

Unlike other nutrients, such as protein and calcium, where requirements are provided in grams per cow per day for specific body weight and milk production levels, fiber “requirements” are merely minimum guidelines aimed at maintaining normal ruminal pH, fiber digestion and milk fat test and preventing SARA and LDA (NRC, 2001). NRC (2001) guidelines for minimum NDF from forage, minimum total diet NDF, and maximum diet NFC are presented in Table 1. Remember that these are fiber minimums and NFC maximums, and not recommended formulation targets for all situations.

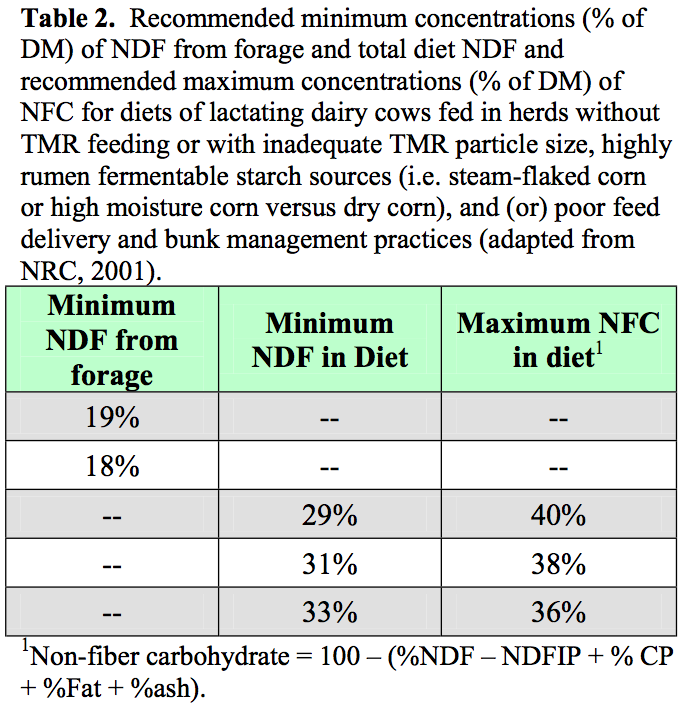

Table 1 applies to diets containing ground corn as the primary starch source fed as TMR of adequate particle size, and assumes good feed delivery and bunk management practices. Greater formulation safety margins (i.e higher NDF from forage and total NDF minimums and lower NFC maximums) should be used in herds without TMR feeding or with inadequate TMR particle size, highly rumen fermentable starch sources (i.e. steam-flaked corn or high moisture corn versus dry corn), and (or) poor feed delivery and bunk management practices (Refer to Table 2). Adequate TMR particle size means having at least 8% to 10% retained on the top screen of the Penn State-Nasco shaker box with less than 50% found on the bottom pan (as-fed basis).

Table 1 applies to diets containing ground corn as the primary starch source fed as TMR of adequate particle size, and assumes good feed delivery and bunk management practices. Greater formulation safety margins (i.e higher NDF from forage and total NDF minimums and lower NFC maximums) should be used in herds without TMR feeding or with inadequate TMR particle size, highly rumen fermentable starch sources (i.e. steam-flaked corn or high moisture corn versus dry corn), and (or) poor feed delivery and bunk management practices (Refer to Table 2). Adequate TMR particle size means having at least 8% to 10% retained on the top screen of the Penn State-Nasco shaker box with less than 50% found on the bottom pan (as-fed basis).

Low alfalfa inventory and high relative costs of fiber and other nutrients from purchased forages versus purchased high-fiber byproducts may create the need or desire to feed minimum forage diets. Diets with less than 19% NDF from forage should contain high-fiber byproducts to increase total diet NDF and reduce diet NFC (Refer to Table 1). Selected high-fiber byproducts and their respective NDF and NFC concentrations are presented in Table 3 for comparison with common forages and grains. In general, replacing grains with high-fiber byproducts has the effect of raising total diet NDF and reducing diet NFC.

Low alfalfa inventory and high relative costs of fiber and other nutrients from purchased forages versus purchased high-fiber byproducts may create the need or desire to feed minimum forage diets. Diets with less than 19% NDF from forage should contain high-fiber byproducts to increase total diet NDF and reduce diet NFC (Refer to Table 1). Selected high-fiber byproducts and their respective NDF and NFC concentrations are presented in Table 3 for comparison with common forages and grains. In general, replacing grains with high-fiber byproducts has the effect of raising total diet NDF and reducing diet NFC.

This practice is positive in low forage diets, as it aids in meeting the total diet NDF and NFC recommendations.

The NDF in high-fiber byproducts is not as effective as the NDF from forage for maintaining normal milk fat test (Armentano and Pereira, 1997). The exception to this is whole cottonseed where the NDF effectiveness factor relative to forage NDF is near 100% (Clark and Armentano, 1993). This is one of the main reasons why whole cottonseed has become such a common feed ingredient in low forage diets. The 15% NDF from forage row in Table 1 is not recommended, because a depression in milk fat test would be expected. Assuming an average NDF concentration for dietary forages of 45%, diet formulation for 19% or 16% NDF from forage would result in diets containing 42% or 35% forage (DM basis), respectively (Refer to Table 4).

Again, greater formulation safety margins (i.e higher NDF from forage and total NDF minimums and lower NFC maximums) should be used in herds without TMR feeding or with inadequate TMR particle size, highly rumen fermentable starch sources (i.e. steam-flaked corn or high moisture corn versus dry corn), and (or) poor feed delivery and bunk management practices (Refer to Table 2).

Again, greater formulation safety margins (i.e higher NDF from forage and total NDF minimums and lower NFC maximums) should be used in herds without TMR feeding or with inadequate TMR particle size, highly rumen fermentable starch sources (i.e. steam-flaked corn or high moisture corn versus dry corn), and (or) poor feed delivery and bunk management practices (Refer to Table 2).

Feed delivery and bunk management

There are numerous errors in feed delivery and bunk management that can occur on commercial dairies. These include: errors in feed sampling and analyses, errors in ingredient DM adjustments, failure to evaluate forage and TMR particle size, failure to evaluate grain moisture content and degree of processing, errors in ingredient feeding rates, mixing errors including over-mixing that causes particle size reduction, and feed sorting).

Close attention should be paid to proper feed delivery and bunk management practices, especially when implementing diet changes aimed at stretching forage supplies. Factors that may make TMR prone to sorting include: DM content and particle size of forage and mix, variation in bulk density of feed ingredients, large pieces of cobs and husks in the corn silage, amount and quality of hay added to mix, improper sequencing of ingredients into the mixer, frequency of feeding and push-up, availability of bunk space, and bunk access time. An on-farm evaluation of sorting should include particle size determination of TMR, bunk mix, and refusals.

If sorting is determined to be a problem, then one or more of the following options may need to be considered: feeding smaller amounts of TMR more frequently, adding less hay to the mix, processing hay finer, using higher quality hay, using hay that is more pliable, processing corn silage, addition of water to dry TMR, and addition of a liquid feed supplement to TMR.

What roughage sources can be substituted for alfalfa haulage?

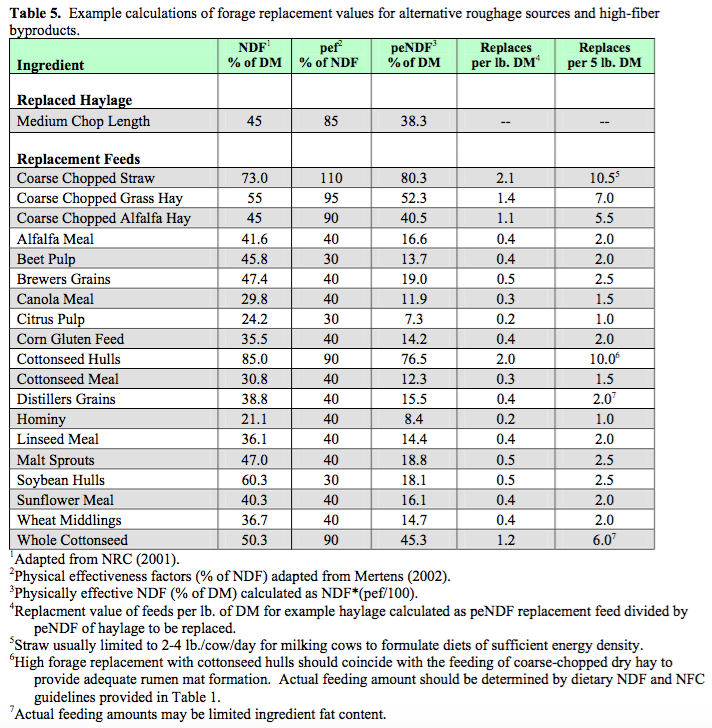

Presented in Table 5 are example calculations of forage replacement values for alternative roughage sources and high-fiber byproducts. The feeding 5 lb./cow/day DM from coarse-chopped hay can replace 5.5 to 7.0 lb./cow/day of haylage DM. In theory, coarse-chopped straw could replace up to 10.5 lb. of haylage DM. But, in practice straw is usually limited to 2 to 4 lb./cow/day for milking cows to formulate diets of sufficient energy density resulting in a potential haylage DM replacement of 4 to 8 lb./cow/day. Feeding 5 lb./cow/day DM from high-fiber byproducts replaces only 2.0/cow/day haylage DM on average,  except for whole cottonseed and cottonseed hulls with haylage replacement vales of 6 and 10 lb./cow/day DM, respectively, at 5 lb./cow/day DM feeding rates. High forage replacement with cottonseed hulls should coincide with the feeding of coarse-chopped dry hay to provide adequate rumen mat formation. Because of poor growing and harvest conditions for the 2002 cotton crop, whole cottonseed quality (moisture, mold, mycotoxins, and free fatty acids) and price need to be closely evaluated when deciding whether or not to feed whole cottonseed or how much to feed. Ration consultants and feed suppliers should be called upon to assist with evaluating the potential for using whole cottonseed to stretch forage supplies.

except for whole cottonseed and cottonseed hulls with haylage replacement vales of 6 and 10 lb./cow/day DM, respectively, at 5 lb./cow/day DM feeding rates. High forage replacement with cottonseed hulls should coincide with the feeding of coarse-chopped dry hay to provide adequate rumen mat formation. Because of poor growing and harvest conditions for the 2002 cotton crop, whole cottonseed quality (moisture, mold, mycotoxins, and free fatty acids) and price need to be closely evaluated when deciding whether or not to feed whole cottonseed or how much to feed. Ration consultants and feed suppliers should be called upon to assist with evaluating the potential for using whole cottonseed to stretch forage supplies.

Suggested feeding limits for selected high-fiber byproducts are presented in Table 6 (Adapted from Howard, 1988). Actual amounts fed should be determined by formulation of diets for requirements and limits for nutrients, such as CP, RUP, RDP, NDF, NFC, fat and P, especially when multiple high-fiber byproducts are used in the same diet. For a detailed discussion of by-product feeds, the following

Suggested feeding limits for selected high-fiber byproducts are presented in Table 6 (Adapted from Howard, 1988). Actual amounts fed should be determined by formulation of diets for requirements and limits for nutrients, such as CP, RUP, RDP, NDF, NFC, fat and P, especially when multiple high-fiber byproducts are used in the same diet. For a detailed discussion of by-product feeds, the following internet publication is recommended: http://cdp.wisc.edu/jenny/crop/byproduct.pdf. Break-even prices for byproduct feeds can be calculated using FEEDVAL6 (Cabrera, Armentano & Shaver, 2016) with blood meal (rumen undegraded protein), urea (rumen degraded protein), shelled corn (energy), tallow (fat), dicalcium phosphate (phosphorus), and calcium carbonate (calcium) as referee feedstuffs. Break-even prices are not provided here, because actual break-even prices vary as prices of the referee feedstuffs change. These change from month to month, year to year, supplier to supplier, and location to location. Calculation of relevant breakeven prices is recommended. The FEEDVAL6 spreadsheet can be obtained at the following internet URL: http://dairymgt.uwex.edu/tools.php. Remember to input currently relevant prices for referee feeds into the spreadsheet so that the calculated breakeven prices from the spreadsheet are relevant.

References

Armentano, L. E., and M. Pereira. 1997. Measuring the effectiveness of fiber by animal response trials. J. Dairy Sci. 80:1416-1425.

Clark, P. W., and L. E. Armentano. 1993. Effectiveness of neutral detergent fiber in whole cottonseed and dried distillers grains compared with alfalfa haylage. J. Dairy Sci. 76:2644-2650.

Howard, W. T. 1988. Here are suggested limits for feed ingredients. Hoard’s Dairyman. March 25, 1988. p. 301.

Mertens, D. R. 2002. Measuring fiber and its effectiveness in ruminant diets. Page 40-66 in Proc. Plains Nutr. Cncl. Spring Conf. San Antonio, TX.

Mertens, D. R. 1997. Creating a system for meeting the fiber requirements of dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 80:1463- 1481.

National Research Council. 2001. Nutrient Requirements of Dairy Cattle. 7th rev. ed. Natl. Acad. Sci., Washington, DC.

Nocek, J. E. 1997. Bovine acidosis: Implications on laminitis. J. Dairy Sci. 80:1005-1028.

![]() Focus on Forage – Vol 5: No. 2

Focus on Forage – Vol 5: No. 2

© University of Wisconsin Board of Regents, 2003

Randy Shaver, Extension Dairy Scientist

University of Wisconsin – Madison

rdshaver@facstaff.wisc.edu