Moldy Hay for Horses1

When haymaking conditions are poor hay may be rained on or left lying in the field for prolonged time periods due to cool and humid conditions which reduced drying rates. The long drying periods with high humidity allow field growth of mold on the hay.

Poor drying weather has also meant that some hay was put up wetter than usual and mold growth occurred in storage. With wet weather and high humidity, normal drying in storage may not occur and hay can retain elevated levels of moisture allowing mold growth. Mold will grow on hay without preservative added at moisture levels above 14% to 15%.  The mold growth produces heat and can result in large amounts of dry matter and TDN (total digestible nutrient) loss – a loss of carbohydrates and binding of proteins. In some cases, heating can be great enough to cause spontaneous combustion and fire. Drying of stored hay (moisture loss) is enhanced by increasing ventilation, creating air spaces between bales, reducing stack size, stacking in alternating directions, and not placing tarp directly over a stack in the field as the tarp traps moisture. Since moisture tends to move up and out the top of a stack of bales, ample head space should be provided above a stack in a barn, allowing moisture to evaporate.

The mold growth produces heat and can result in large amounts of dry matter and TDN (total digestible nutrient) loss – a loss of carbohydrates and binding of proteins. In some cases, heating can be great enough to cause spontaneous combustion and fire. Drying of stored hay (moisture loss) is enhanced by increasing ventilation, creating air spaces between bales, reducing stack size, stacking in alternating directions, and not placing tarp directly over a stack in the field as the tarp traps moisture. Since moisture tends to move up and out the top of a stack of bales, ample head space should be provided above a stack in a barn, allowing moisture to evaporate.

Molds commonly found in hay include Alternaria, Aspergillus, Cladosporum, Fusarium, Mucor, Penicillium, and Rhizopus. These molds can produce spores that cause respiratory problems, especially in horses and, under some conditions, will produce mycotoxins.

Horses are particularly sensitive to dust from mold spores and can get a respiratory disease, like asthma in humans, called Recurrent Airway Obstruction (RAO), commonly referred to as heaves. A horse with RAO will have a normal temperature and a good appetite, but will often have decreased exercise tolerance, coughing and nasal discharge. Labored breathing occurs during exercise and, in some cases, while at rest. Hypertrophy of the abdominal oblique muscle used for expiration creates the characteristic ‘heave line’ seen on horses with RAO. Some horses are highly allergic to certain mold spores while others seem to be minimally affected. Even among horses with symptoms of RAO, can be variations of their sensitivity levels to additional detrimental stimuli such as dust and poor air quality. To decrease exposure, horses should spend more time outside on pasture rather than on a dusty paddock or inside the barn. Additional ways to reduce dust exposure are as follows:

- Use dust-free bedding such as shredded paper or rubber mats

- Do not feed dusty and moldy hay and grains

- Place feed at a lower level so particles are not inhaled through the nostrils

- Keep your horse out of the stable when you are cleaning and sweeping to reduce exposure to dust

- Feed hay outside to minimize dust problems. In severe cases, hay may be replaced by hay cubes

- Soak dusty hay for 5 to 30 minutes before feeding so that the horse can eat it while it’s wet

- Store hay away from your horse as much as possible and ensure any hay in the vicinity is kept dry to reduce mold

- If the horse is housed indoors, ensure that there is good, draft-free ventilation through the stable

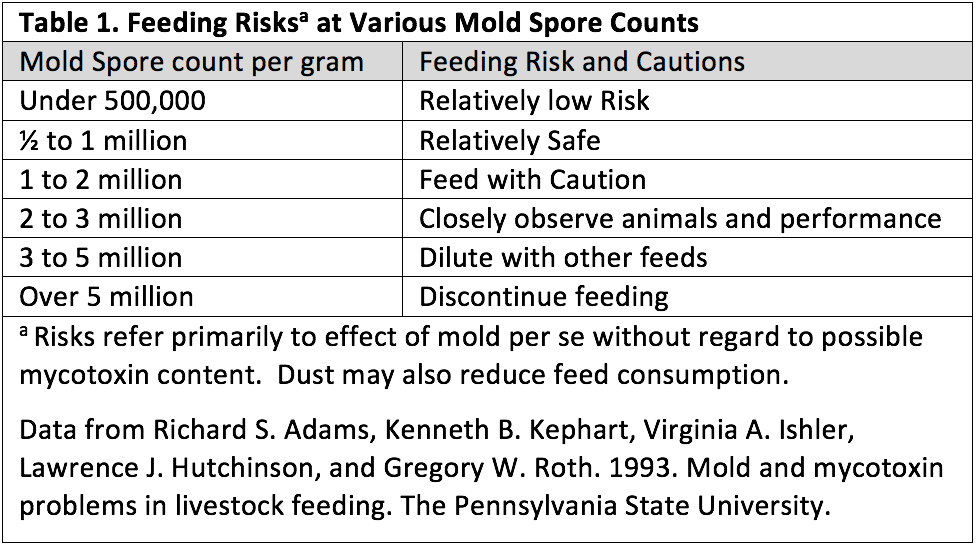

Sometimes mold spores are counted on moldy feeds to obtain an indication of the extent of molding and relative risks in feeding them. Table 1 contains classification of risks at various mold spore counts.

Sometimes mold spores are counted on moldy feeds to obtain an indication of the extent of molding and relative risks in feeding them. Table 1 contains classification of risks at various mold spore counts.

While most molds do not produce mycotoxins, the presence of mold indicates the possibility of mycotoxin presence and animals being fed moldy hay should be watched carefully for mycotoxin symptoms.

Mycotoxins effects on animals:

- Intake reduction or feed refusal;

- Reduced nutrient absorption and impaired metabolism, including altered digestion and microbial growth, diarrhea, intestinal irritation, reduced production, lower fertility, abortions, lethargy, and increased morbidity;

- Alterations in the endocrine and exocrine systems;

- Suppression of the immune system which predisposes horses to many diseases. A suppressed immune system may also cause lack of response to medications and failure of vaccine programs;

- Cellular death causing organ damage

If you have mold in hay, watch for the symptoms mentioned above. If hay is dusty, take care in feeding to sensitive animals and those, especially, in areas with poor ventilation. If hay is moldy, the recommendation is to not feed it to horses at all. If symptoms of mycotoxin poisoning are observed (which can occur from mold not visible), check with a nutritionist to make sure the ration is properly balanced and with a veterinarian to eliminate other disease/health problems. Quick test kits (ELISA kits) are available to determine presence of a limited number mycotoxins but they can give false positives. Some forage testing laboratories will provide other mycotoxin tests. Often, the best strategy is to remove a suspected mycotoxin-contaminated feedstuff from the diet and see if symptoms disappear. If mycotoxins are present, the feedstuff can often be fed at a diluted rate and/or with approved feed additives.

In Summary:

- Most moldy hay problems are due to mold spores which can produce respiratory disease in horses

- Many of the commonly diagnosed mycotoxins from molds are produced in the field when harvest is delayed

- If a mycotoxin problem is suspected, a comprehensive review of animal nutrition and health is essential — i.e. problems blamed on mycotoxins may be other disorders or nutritional issues. Diagnosing a mycotoxin problem is difficult and often involves the elimination of other possible factors

- The physical dust problem associated with moldy forage can be reduced by feeding in a well ventilated area, mixing with a high moisture feed or wetting the hay, but these will not reduce mycotoxins if present

![]() ¹Written by Dan Undersander, Univ. of Wisconsin (djunders@wisc.edu); Marvin Hall, The Pennsylvania State Univ. (mhh2@psu.edu); Richard Leep, Michigan State Univ. (leep@msu.edu); Krishona Martinson, Univ. of Minnesota (krishona@umn.edu); J. Liv. Sandberg, Univ. of Wisconsin (sandberg@ansci.wisc.edu); Glenn Shewmaker, Univ. of Idaho (gshew@uidaho.edu); Don Westerhaus, Kemin AgriFoods North America (Don.Westerhaus@kemin.com), and Lon Whitlow, North Carolina State Univ. (lon_whitlow@ncsu.edu).

¹Written by Dan Undersander, Univ. of Wisconsin (djunders@wisc.edu); Marvin Hall, The Pennsylvania State Univ. (mhh2@psu.edu); Richard Leep, Michigan State Univ. (leep@msu.edu); Krishona Martinson, Univ. of Minnesota (krishona@umn.edu); J. Liv. Sandberg, Univ. of Wisconsin (sandberg@ansci.wisc.edu); Glenn Shewmaker, Univ. of Idaho (gshew@uidaho.edu); Don Westerhaus, Kemin AgriFoods North America (Don.Westerhaus@kemin.com), and Lon Whitlow, North Carolina State Univ. (lon_whitlow@ncsu.edu).