Through good forest management practices, land managers can decrease the likelihood and severity of defoliation during a spongy moth (Lymantria dispar) outbreak. These practices improve stand vigor, giving trees a better chance of survival following defoliation. The following publications describe management options for woodlots dominated by oaks and other deciduous trees:

- Spongy Moth Silvicultural Guidelines for Wisconsin (PUB-FR-123-97) [PDF]

- Forestry Facts: Forest Management Strategies to Minimize the Impact of Spongy Moth (No. 83) [PDF]

Should you spray?

Your decision to spray should be guided by three considerations: how you use your woodlot, the predicted severity of defoliation, and the expense of treating.

Woodlot use

Conifer pulpwood production. Conifer plantations are best protected by removing preferred host trees, such as oak, witch hazel, amelanchier, and aspen, from their borders and understory.

Aesthetic or recreational use. Since appearances are important, you may wish to suppress spongy moth outbreaks in your woodlot, especially if your home is there. The cost of spraying may be significant but it is probably less than the cost of removing dead trees from around your house.

Hunting. Oaks are an important source of food for many game animals and defoliation will reduce acorn crops for several years. Hunters may wish to protect their acorn crop by suppressing spongy moth outbreaks.

Providing habitat for non-game wildlife. While some trees may die as a result of defoliation, they will go on to provide important nest and den snags for cavity-dependent species. Because our younger forests often have few snags, the formation of dead material following an outbreak of spongy moths can actually help increase the diversity and abundance of bird populations. Landowners whose primary interest is nongame wildlife may decide to allow outbreaks to go unchecked.

Predicting defoliation

You can predict next year’s level of defoliation by spongy moth caterpillars by counting the number of egg masses on your property. Egg masses are laid in August, but the best time to conduct a survey is after leaves have fallen.

To conduct a survey you will need:

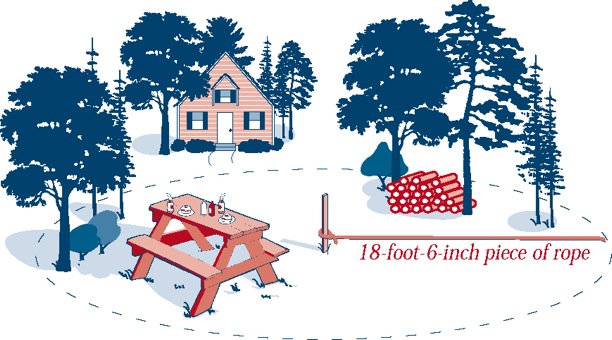

- An 18-foot, 6-inch length of string attached to a stake

- Binoculars

- A note pad and pencil

- A map of the area

- Select a patch of trees that is typical of the area you are concerned about.

- Set the stake and use the string to measure a circle with a radius of 18 feet, 6 inches.

- Search the circle for all egg masses. Use the binoculars to look for egg masses high on the trees, especially the undersides of larger branches. Also check all items on the ground such as picnic tables and woodpiles.

- Note down the number of egg masses you found and the location of your survey circle.

- Move at least 150 feet away from your first circle and take another survey. Space out your survey circles throughout the area you are concerned about.

- Calculate the average number of egg masses you found in each of your survey circles. An average of greater than 25 egg masses in a woodlot or forest indicates a high likelihood of spongy moth caterpillars causing defoliation in this area. Examine your map to see if there is any pattern to the number of egg masses found. If you see a patch of higher egg mass numbers within the area you surveyed, you may want to treat that area separately and average the number of egg masses found within that area. Or if the number of egg masses increases in one direction, you may want to take more surveys in that area to determine the extent of the land that could be damaged by spongy moth next year.

Economic considerations

Even if more than 50% defoliation is predicted for your woodlot, it may not make economic sense to treat. In the first year of defoliation, weak trees die. This can be a benefit if your woodlot is overstocked with many suppressed trees. When these weak trees die, the remaining trees face less competition for sunlight, water, and nutrients. In Pennsylvania, researchers found dramatic increases in growth of red oaks following an attack by spongy moth. On the other hand, in a stand dominated by very old white oaks already suffering from some crown dieback, severe defoliation will kill many of these trees. Treatment will be essential to save the stand.

To decide whether treatment makes sense for your situation, consult a Wisconsin DNR forester.